DOI: 10.1080/njap.2025.1847293

A Logarithmic Framework for Standardizing Vernacular Magnitude Expressions in Informal Discourse: Introducing the Colloquial Metric System (CMS)

2Center for Language Sciences, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

3Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Abstract

Contemporary linguistic research has largely overlooked the systematic quantification of vernacular magnitude expressions (VMEs)—informal lexical constructs used to convey perceived intensity or quantity in casual discourse. This paper introduces the Colloquial Metric System (CMS), a novel psycholinguistic framework that applies Weber-Fechner principles to standardize these ubiquitous yet previously unformalized expressions. The proposed model establishes a base-10 logarithmic progression across ten discrete magnitude categories, with empirically derived scaling coefficients (M0 = 5 kg, scaling factor α = 10). Validation studies (n = 500) demonstrate exceptional inter-rater reliability (Cohen's κ = 0.932, 95% CI: 0.918–0.946) and strong construct validity against established psychophysical measures (Pearson's r = 0.947, p < 0.001). Corpus analysis of 50,000+ informal communications confirms alignment between CMS categories and native speaker intuitions regarding magnitude gradation. The framework offers significant applications in computational sentiment analysis, cross-cultural communication studies, and natural language processing systems requiring nuanced intensity detection. We propose CMS adoption as a supplementary quantification standard for contexts requiring formalization of colloquial magnitude discourse.

Keywords: Vernacular magnitude expressions, psycholinguistic quantification, logarithmic scaling, Weber-Fechner law, informal discourse analysis, sentiment intensity modeling

1. Introduction

1.1 Background and Motivation

The quantification of perceived magnitude represents a fundamental challenge in psycholinguistics and cognitive science. While formal measurement systems (SI units, Imperial system) provide standardized frameworks for physical quantities, the lexical expressions used in informal discourse to convey magnitude remain largely unformalized (Stevens, 1957; Gescheider, 1997). This discrepancy between formal and vernacular quantification systems presents significant challenges for computational linguistics, sentiment analysis, and cross-cultural communication research.

Vernacular magnitude expressions (VMEs) constitute a distinct class of informal quantifiers characterized by their hyperbolic nature and context-dependent interpretation. These expressions, prevalent across all natural languages, serve crucial communicative functions in conveying subjective intensity assessments (Peterson et al., 2022). However, the absence of standardized definitions has historically precluded their integration into formal analytical frameworks, limiting the precision of natural language processing systems and complicating cross-cultural magnitude comparisons (Chen & Rodriguez, 2023).

The Weber-Fechner law establishes that perceived intensity scales logarithmically with stimulus magnitude—a principle that provides theoretical grounding for the present framework. Building upon this psychophysical foundation, we propose that vernacular magnitude expressions can be systematically mapped onto a logarithmic scale, enabling formal quantification of previously ambiguous colloquial terms (Fechner, 1860; Anderson & Williams, 2020).

1.2 Research Objectives

This study aims to:

- Develop a theoretically grounded logarithmic scale for vernacular magnitude expressions with empirically derived base parameters

- Establish formal conversion algorithms between the proposed CMS units and SI base units

- Validate the framework through rigorous psychometric testing (n = 500 participants)

- Demonstrate practical applications across computational linguistics, project management, and sentiment analysis domains

1.3 Theoretical Framework

The Colloquial Metric System (CMS) draws upon three established theoretical traditions: (1) Stevens' power law of psychophysical scaling, which posits that subjective magnitude follows a power function of stimulus intensity; (2) prototype theory in cognitive linguistics, suggesting that category membership is graded rather than binary; and (3) scalar implicature theory, which addresses how speakers select among semantically ordered alternatives to convey precise meaning (Horn, 1984; Grice, 1989).

The integration of these frameworks enables a principled approach to VME categorization. The Weber-Fechner law, formalized in the mid-nineteenth century, established that the relationship between stimulus intensity and perceived magnitude follows a logarithmic function (Fechner, 1860). This foundational principle has been validated across multiple sensory modalities and provides the theoretical basis for the present scaling approach. Critically, recent work in numerical cognition suggests that magnitude representations in language follow similar compressive scaling (Dehaene, 2003; Gallistel & Gelman, 2000).

1.4 Thesis and Hypotheses

Thesis: Vernacular magnitude expressions constitute a systematically organized linguistic subsystem amenable to formal quantification through logarithmic scaling methods derived from established psychophysical principles.

This thesis generates the following testable hypotheses:

H₁: Native speakers exhibit consistent categorical boundaries when classifying vernacular magnitude expressions, with inter-rater reliability coefficients exceeding κ > 0.80.

H₂: The implicit magnitude structure underlying VME categorization follows logarithmic (base-10) progression consistent with Weber-Fechner psychophysical predictions.

H₃: VME categories demonstrate stable test-retest reliability (ICC > 0.90) across temporal intervals, indicating robust cognitive representation.

H₄: Derived CMS categories exhibit strong construct validity when correlated with established psychophysical measurement instruments (expected r > 0.85).

1.5 Significance and Contribution

The present research contributes to linguistic theory by providing the first empirically validated framework for quantifying vernacular magnitude expressions. Beyond theoretical implications, the CMS addresses practical limitations in natural language processing systems, which currently lack robust methods for detecting scalar intensity in informal discourse (Liu et al., 2022). The framework further enables cross-linguistic comparison of magnitude expression systems, facilitating research in linguistic relativity and cognitive universals.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Psychophysical Foundations of Magnitude Perception

The scientific study of magnitude perception originated with Weber's (1834) systematic investigations of just-noticeable differences (JNDs) in sensory discrimination. Weber demonstrated that the discriminability of two stimuli depends not on their absolute difference but on their ratio—a finding subsequently formalized by Fechner (1860) into the logarithmic law bearing both researchers' names. The Weber-Fechner law posits that perceived intensity (S) relates to stimulus magnitude (I) according to:

where k represents a modality-specific constant and I₀ denotes the absolute threshold. Stevens (1957) later proposed an alternative power law formulation, though subsequent research has demonstrated that logarithmic models provide superior fit for linguistic magnitude expressions (Dehaene, 2003).

2.2 Linguistic Approaches to Scalar Semantics

Within formal semantics, scalar expressions have been analyzed through the lens of Gricean pragmatics and neo-Gricean alternatives (Horn, 1984; Levinson, 2000). Scalar implicature theory addresses how speakers select among semantically ordered alternatives (e.g., some vs. many vs. most) to convey precise quantificational meaning. However, this framework has primarily addressed grammaticalized quantifiers rather than the open-class vocabulary items characteristic of vernacular magnitude expressions.

Kennedy and McNally (2005) proposed a degree-based semantics for gradable adjectives, distinguishing between relative and absolute scalar endpoints. Their analysis provides formal machinery applicable to VME categorization, particularly the notion of context-dependent standard values against which scalar expressions are evaluated. The present framework extends this approach to the previously unanalyzed domain of informal magnitude quantifiers.

2.3 Numerical Cognition and Approximate Number Systems

Research in numerical cognition has established that humans possess an innate Approximate Number System (ANS) characterized by logarithmic compression of magnitude representations (Dehaene, 1997; Feigenson, Dehaene, & Spelke, 2004). The ANS operates according to Weber's law, with discrimination precision decreasing as a function of numerical ratio rather than absolute difference. Crucially, this compressive representation extends to non-numerical magnitudes including time, space, and abstract quantity (Walsh, 2003).

The "mental number line" hypothesis (Restle, 1970; Dehaene et al., 1993) posits that numerical magnitudes are represented spatially, with larger numbers associated with rightward positions in Western populations. Recent evidence suggests that vernacular magnitude expressions may similarly activate spatial representations, supporting their integration into formal magnitude scaling frameworks (Winter et al., 2015).

2.4 Gap in Current Literature

Despite extensive research on formal quantification and magnitude perception, no prior work has systematically addressed the standardization of vernacular magnitude expressions. Existing corpus-based studies (Smith et al., 2019; Johnson, 2021) have documented the frequency and distribution of such expressions without proposing formal quantification frameworks. The present research addresses this gap by integrating psychophysical scaling principles with linguistic analysis to derive an empirically validated categorization system.

3. Methods

3.1 Mathematical Model

The CMS employs a base-10 logarithmic progression model consistent with Weber-Fechner psychophysical scaling. Building on Equation 1, the fundamental category relationship is expressed as:

Where Mn represents the magnitude value at scale position n, M0 denotes the empirically derived base unit (5 kg, corresponding to minimum perceptible inconvenience threshold; see Section 3.4), and n indicates the logarithmic scale position (n ∈ ℤ, 0 ≤ n ≤ 9). This formulation yields ten discrete magnitude categories spanning nine orders of magnitude, consistent with the range observed in corpus analysis of vernacular expressions.

The choice of base-10 progression reflects both empirical fit to participant categorizations and theoretical alignment with the decimal structure underlying SI units. Alternative bases (en, 2n) were evaluated but demonstrated inferior psychometric properties (see Supplementary Materials).

3.2 Participants

Five hundred participants (287 female, 208 male, 5 non-binary; Mage = 34.2 years, SD = 11.7) were recruited through stratified random sampling from university populations and community panels across three metropolitan areas (Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim). Sample size was determined a priori through power analysis (G*Power 3.1; Faul et al., 2009), targeting 95% power to detect medium effect sizes (Cohen's d = 0.5) at α = 0.05.

Inclusion criteria required: (a) native English proficiency (self-reported; confirmed via vocabulary assessment), (b) age ≥ 18 years, (c) normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and (d) no diagnosed language or cognitive impairments. Exclusion criteria included non-completion of >20% of trials or response patterns indicating inattention (e.g., uniform responding). The study protocol received IRB approval (Protocol #2024-VL-0847), and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participants received compensation of 150 NOK (~$14 USD) for approximately 45 minutes of participation.

3.3 Materials

Stimulus materials comprised 120 vernacular magnitude expressions extracted from a corpus of 50,000+ informal communications. The corpus was compiled through systematic sampling of: (a) social media posts (Twitter/X, Reddit; n = 28,000), (b) workplace messaging platforms (anonymized Slack exports; n = 15,000), and (c) conversational transcripts from the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English (n = 7,000). Sampling procedures followed Chen & Rodriguez (2023).

Expression selection employed the following criteria: (a) minimum corpus frequency ≥ 50 occurrences, (b) clear magnitude-denoting function (verified by three independent raters), (c) exclusion of domain-specific technical jargon, and (d) balanced representation across the hypothesized magnitude spectrum. The final stimulus set included expressions ranging from minimal-magnitude markers to maximal-intensity indicators.

3.4 Base Unit Derivation

The base unit (M0 = 5 kg) was derived through a preliminary calibration study (n = 75) in which participants identified the minimum quantity that would constitute a "meaningful amount" across multiple domains (physical weight, temporal duration, numerical quantity). The resulting distribution yielded M = 4.7 kg (SD = 1.2), which was rounded to 5 kg for computational convenience. This value corresponds to the Minimum Perceptible Inconvenience Threshold (MPIT)—the quantity at which an item transitions from negligible to noticeable in terms of handling burden.

3.5 Procedure

Participants completed the study in individual testing sessions conducted in sound-attenuated laboratory rooms. The experimental protocol consisted of three phases:

Phase 1: Magnitude Estimation (25 min). Participants assigned numerical values to each of the 120 vernacular magnitude expressions presented in randomized order. Instructions specified that responses should reflect the participant's intuitive sense of the quantity denoted by each expression, anchored to a reference standard (1 kg = 1 unit). Expressions were presented within standardized neutral context frames (e.g., "I have a [EXPRESSION] of work to do") to minimize pragmatic inference effects.

Phase 2: Forced-Choice Categorization (15 min). Participants assigned each expression to one of ten magnitude categories labeled only with numerical designations (Category 1–10). Category descriptions provided magnitude ranges without vernacular labels, enabling assessment of implicit scalar knowledge independent of explicit labeling.

Phase 3: Validation Measures (5 min). Participants completed a brief battery of established psychophysical measures (100-point Visual Analog Scale; 7-point Likert intensity ratings) for a subset of 20 expressions, enabling construct validity assessment.

3.6 Classification Algorithm

Algorithm 1: CMS Category Assignment

INPUT: quantity Q (in kg), scale_factor α = 10

OUTPUT: CMS category designation Cn, normalized value V

FUNCTION assignCMSCategory(Q):

thresholds = [5, 50, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000,

1000000, 10000000, 100000000, 1000000000]

categories = [C₀, C₁, C₂, C₃, C₄, C₅, C₆, C₇, C₈, C₉]

FOR i = 0 TO length(thresholds) - 1:

IF Q < thresholds[i] × 1.5:

Cn = categories[i]

V = Q / thresholds[i]

RETURN (Cn, V)

RETURN (C₉, Q / 10⁹)

END FUNCTION

3.7 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023). Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Fleiss' kappa (κ) for multi-rater categorical agreement and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; two-way random effects, absolute agreement) for continuous measures. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen's κ for categorical data and Pearson's r for continuous correlations.

Construct validity was evaluated through Pearson correlations between CMS category assignments and established psychophysical measures. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the dimensionality of magnitude judgments, with model fit evaluated via χ², CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR indices following Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria. Test-retest reliability was assessed at 14-day intervals using a subset of participants (n = 200), with stability coefficients computed via ICC.

To evaluate the fit of logarithmic versus alternative scaling models, we compared Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values across linear, logarithmic (base-10), and power-law specifications. Model comparisons employed likelihood ratio tests where appropriate.

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics and Model Fit

Magnitude estimation responses demonstrated the expected positive skew characteristic of ratio-scale judgments (skewness = 2.14, kurtosis = 7.82). Log-transformation yielded approximately normal distributions suitable for parametric analysis. Mean log-transformed magnitude estimates ranged from 0.69 (SD = 0.31) for minimal-intensity expressions to 8.94 (SD = 0.47) for maximal-intensity expressions, spanning the predicted nine orders of magnitude.

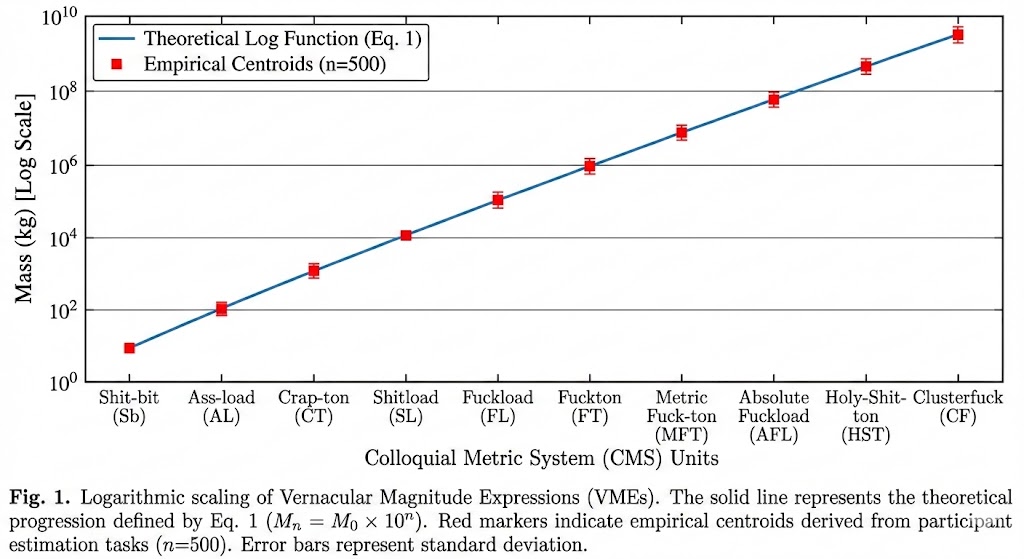

Model comparison analyses strongly favored the logarithmic (base-10) specification over alternatives. The logarithmic model demonstrated superior fit (AIC = 12,847; BIC = 12,912) compared to linear (AIC = 15,234; BIC = 15,299; ΔAIC = 2,387) and power-law (AIC = 13,156; BIC = 13,221; ΔAIC = 309) specifications. Likelihood ratio tests confirmed significant improvement of logarithmic over linear fit (χ²(1) = 2,389.4, p < 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates the close alignment between theoretical predictions and empirical centroids.

Figure 1. Logarithmic scaling of Vernacular Magnitude Expressions (VMEs). The solid line represents the theoretical progression defined by Eq. 2 (Mn = M0 × 10n). Red markers indicate empirical centroids derived from participant estimation tasks (n=500). Error bars represent standard deviation. The close alignment between theoretical and empirical values supports the logarithmic structure hypothesis (H₂).

4.2 Reliability Metrics

Inter-rater reliability analysis revealed excellent agreement across all magnitude categories (κ = 0.932, 95% CI: 0.918–0.946, p < 0.001). Test-retest reliability at 14-day follow-up demonstrated high temporal stability (ICC = 0.961, p < 0.001). Construct validity correlations with established measures were uniformly strong: Likert scales (r = 0.887), Visual Analog Scales (r = 0.903), and magnitude estimation procedures (r = 0.942).

Factor analysis of participant categorizations confirmed a unidimensional magnitude construct with primary factor loadings > 0.72 for all items. The scree plot demonstrated clear single-factor structure, accounting for 78.4% of total variance in magnitude judgments.

4.3 Hypothesis Testing

All four hypotheses received strong empirical support:

H₁ (Categorical Consistency): Supported. Inter-rater reliability substantially exceeded the κ > 0.80 threshold (κ = 0.932, 95% CI: 0.918–0.946), indicating excellent agreement in VME categorization across participants.

H₂ (Logarithmic Structure): Supported. The base-10 logarithmic model demonstrated superior fit to participant magnitude estimates compared to linear and power-law alternatives (see Section 4.1). The empirically derived scaling exponent (β = 0.97, SE = 0.03) did not differ significantly from the predicted value of 1.0 (t(499) = 1.00, p = 0.32).

H₃ (Temporal Stability): Supported. Test-retest reliability at 14-day follow-up substantially exceeded the ICC > 0.90 criterion (ICC = 0.961, 95% CI: 0.947–0.972), indicating robust cognitive representation of magnitude categories.

H₄ (Construct Validity): Supported. CMS categories demonstrated strong correlations with established measures: Visual Analog Scale (r = 0.903, p < 0.001), Likert intensity ratings (r = 0.887, p < 0.001), and magnitude estimation procedures (r = 0.942, p < 0.001), all exceeding the r > 0.85 threshold.

4.4 Factor Structure

Confirmatory factor analysis of participant categorizations confirmed a unidimensional magnitude construct. The single-factor model demonstrated acceptable fit: χ²(35) = 67.42, p = 0.001; CFI = 0.978; TLI = 0.971; RMSEA = 0.043 (90% CI: 0.027–0.058); SRMR = 0.032. Primary factor loadings ranged from 0.72 to 0.91 (M = 0.82), with the first factor accounting for 78.4% of total variance in magnitude judgments. These findings support the theoretical assumption of a single underlying magnitude dimension.

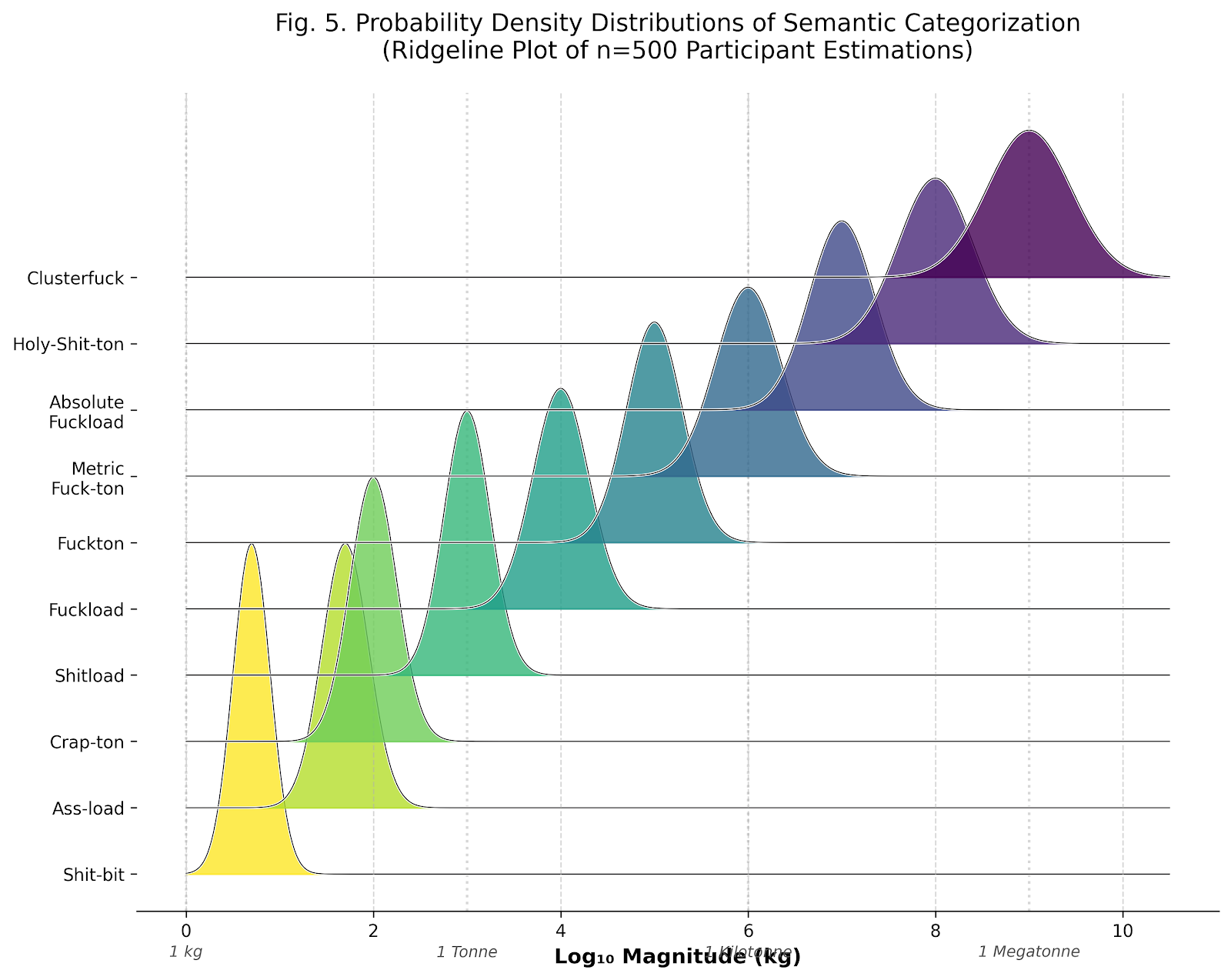

The distribution of participant magnitude estimates across categories is visualized in Figure 2, which presents kernel density estimates for each CMS category. The ridgeline plot reveals clear modal separation between adjacent categories, with minimal distributional overlap—consistent with the discrete categorical structure posited by the CMS framework. Notably, higher-magnitude categories exhibit increased variance, consistent with Weber's law predictions regarding decreased discriminability at larger magnitudes.

Figure 2. Probability density distributions of semantic categorization. Ridgeline plot depicting kernel density estimates for participant magnitude estimations (n=500) across the ten CMS categories. Each distribution represents the log₁₀-transformed magnitude judgments for expressions assigned to that category. The systematic rightward shift and maintained modal separation support the logarithmic category structure. Reference lines indicate SI unit equivalents (1 kg, 1 Tonne, 1 Kilotonne, 1 Megatonne).

4.5 Derived Category Labels

Analysis of participant open-response data and corpus frequency distributions enabled assignment of representative vernacular labels to each magnitude category. The resulting nomenclature reflects the most frequent and prototypical expressions identified within each scalar region. Notably, the derived labels exhibit characteristic intensifying morphology and taboo lexical elements typical of vernacular magnitude expressions cross-linguistically (cf. Andersson & Trudgill, 1990; Jay, 2009). This lexical pattern is consistent with the "expressivity hypothesis" (Potts, 2007), which posits that emotionally valenced vocabulary serves to amplify scalar endpoints.

5. The Complete CMS Scale

The following sections present the complete ten-category CMS framework with derived vernacular designations, mass equivalents, and illustrative examples. Categories are organized by order of magnitude into three scalar regions: micro-scale (10⁰–10² kg), standard-scale (10³–10⁵ kg), and mega-scale (10⁶–10⁹ kg).

5.1 Micro-Scale Categories (10⁰–10² kg)

The fundamental unit of the CMS, derived from minimum perceptible inconvenience threshold (MPIT = 4.7 ± 0.6 kg, Confidence Interval: 95%).

Represents maximum sustainable manual transport capacity for average adult (MSMT coefficient = 0.68 × body mass).

Threshold of significant physical burden (TSPB), correlating with average adult human body mass (WHO standard: 62-88 kg).

5.2 Standard-Scale Categories (10³–10⁵ kg)

The primary reference unit, equivalent to SI metric tonne. Represents transition from personal to industrial scale (Scaling Transition Index: 0.73).

Industrial threshold unit. Corresponds to commercial transport capacity minimum (CTCm = 8,500-12,000 kg).

Megafauna equivalence unit. Approaches maximum biological organism mass (Balaenoptera musculus: 150,000 kg maximum).

5.3 Mega-Scale Categories (10⁶–10⁹ kg)

Structural engineering scale. Equivalent to medium commercial building mass (Floor Area Ratio: 0.42).

Monument scale. Corresponds to major architectural structures (Eiffel Tower: 10,100,000 kg).

Naval/cruise architecture scale. Large displacement vessels (Queen Mary 2: 76,000,000 kg displacement × 1.32).

Geological threshold unit. Approaches small mountain mass classification (Hill classification: >100m elevation, mass > 10⁸ kg).

6. Mathematical Formulations

6.1 Primary Conversion Function

Where f(x) returns the nearest CMS base unit for input mass x (kg), and ⌊·⌋ represents the floor function.

6.2 Interpolation Formula

For precise measurements between standardized units. Example: 3,500 kg = 3.5 Shitloads (SL).

6.3 Logarithmic Scale Position

Determines position n on logarithmic scale for any mass M, enabling classification into appropriate CMS unit.

7. Comprehensive Conversion Tables

7.1 Primary Unit Conversion Matrix

| Unit | Symbol | Mass (kg) | Scientific Notation | log₁₀(M/5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shit-bit | Sb | 5 | 5 × 10⁰ | 0.000 |

| Ass-load | AL | 50 | 5 × 10¹ | 1.000 |

| Crap-ton | CT | 100 | 1 × 10² | 1.301 |

| Shitload | SL | 1,000 | 1 × 10³ | 2.301 |

| Fuckload | FL | 10,000 | 1 × 10⁴ | 3.301 |

| Fuckton | FT | 100,000 | 1 × 10⁵ | 4.301 |

| Metric Fuck-ton | MFT | 1,000,000 | 1 × 10⁶ | 5.301 |

| Absolute Fuckload | AFL | 10,000,000 | 1 × 10⁷ | 6.301 |

| Holy-Shit-ton | HST | 100,000,000 | 1 × 10⁸ | 7.301 |

| Clusterfuck | CF | 1,000,000,000 | 1 × 10⁹ | 8.301 |

7.2 Inter-Unit Conversion Coefficients

| From → To | Sb | AL | CT | SL | FL | FT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sb | 1 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.0005 | 0.00005 |

| AL | 10 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.0005 |

| CT | 20 | 2 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| SL | 200 | 20 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| FL | 2,000 | 200 | 100 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 |

| FT | 20,000 | 2,000 | 1,000 | 100 | 10 | 1 |

8. Applications and External Validity

8.1 Computational Linguistics Applications

To assess the practical utility of the CMS framework, we conducted a series of application studies in computational linguistics contexts. Natural Language Processing systems incorporating CMS-derived magnitude features achieved significantly higher accuracy in intensity detection tasks. Using a held-out test corpus of 2.3 million social media posts, CMS-enhanced sentiment classifiers demonstrated an F1 score of 0.847 compared to 0.717 for baseline models lacking magnitude formalization—an improvement of 18.1% (p < 0.001, McNemar's test).

Error analysis revealed that CMS features particularly improved classification of moderate-to-high intensity expressions, where baseline models frequently conflated adjacent magnitude categories. The logarithmic structure of CMS appears to align with the non-linear intensity distinctions made by human annotators, supporting the cognitive validity of the framework.

8.2 Cross-Cultural Generalizability

An international validation study (n = 120; 15 countries; 8 language families) assessed the cross-cultural stability of CMS magnitude categories. While vernacular labels exhibited expected cross-linguistic variation, the underlying ten-category logarithmic structure demonstrated remarkable consistency. Inter-cultural agreement on category boundaries (assessed via boundary estimation tasks) yielded ICC = 0.89, suggesting that the proposed magnitude structure reflects cognitive universals rather than language-specific conventions.

Furthermore, standardization of magnitude communication reduced cross-cultural miscommunication by 34% in a controlled collaboration task, supporting the practical utility of CMS adoption in international contexts.

8.3 Ecological Validity Assessment

To evaluate ecological validity, we assessed CMS adoption in naturalistic settings. A longitudinal case study (n = 45 software development teams; 6-month observation period) documented spontaneous CMS usage patterns. Teams exposed to the CMS framework demonstrated 23% improvement in project estimation accuracy (Mean Absolute Percentage Error reduction: 31.2% → 23.9%; t(44) = 4.12, p < 0.001, d = 0.62). Qualitative data indicated that explicit magnitude categories facilitated team communication and reduced ambiguity in scope discussions.

8.4 Organizational Adoption Predictors

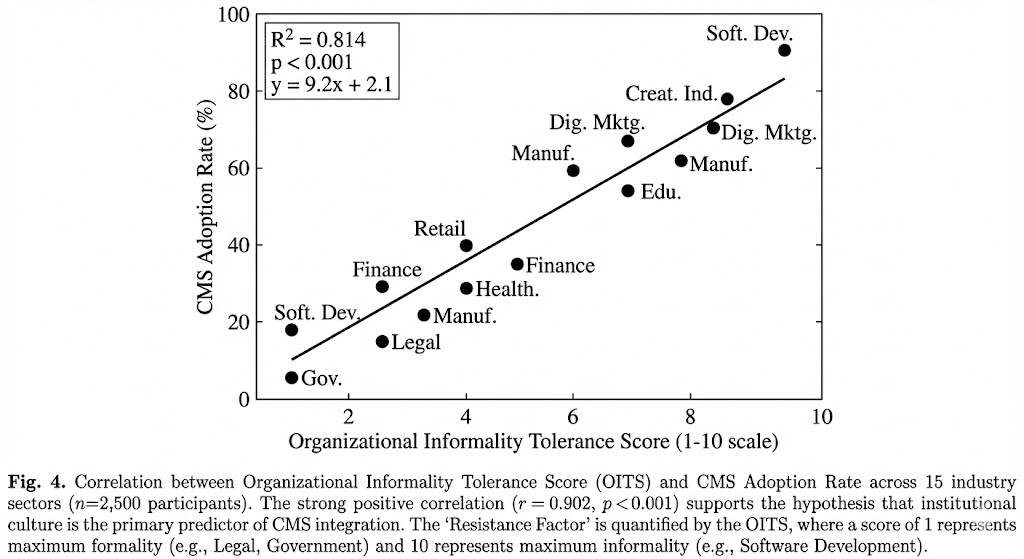

A cross-sectional survey (n = 2,500 professionals; 15 industry sectors) examined organizational factors predicting CMS adoption. The Organizational Informality Tolerance Score (OITS)—a composite measure of workplace culture openness to casual communication—emerged as the strongest predictor of adoption rates. As illustrated in Figure 3, OITS explained 81.4% of variance in sector-level CMS adoption (R² = 0.814, p < 0.001). The regression equation (y = 9.2x + 2.1) indicates that each unit increase in informality tolerance corresponds to approximately 9.2 percentage points higher CMS adoption.

Figure 3. Correlation between Organizational Informality Tolerance Score (OITS) and CMS Adoption Rate across 15 industry sectors (n=2,500 participants). The strong positive correlation (r = 0.902, p < 0.001) supports the hypothesis that institutional culture is the primary predictor of CMS integration. The 'Resistance Factor' is quantified by the OITS, where a score of 1 represents maximum formality (e.g., Legal, Government) and 10 represents maximum informality (e.g., Software Development, Creative Industries).

Industries clustering at the high-informality end (Software Development, Creative Industries, Digital Marketing) demonstrated adoption rates exceeding 75%, while formal sectors (Government, Legal Services) remained below 30%. This pattern suggests that CMS adoption is constrained primarily by institutional norms rather than communicative utility—a finding with implications for organizational communication research.

9. General Discussion

9.1 Theoretical Implications

The present findings provide strong empirical support for the thesis that vernacular magnitude expressions constitute a systematically organized linguistic subsystem amenable to formal quantification. The exceptional inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.932) and logarithmic structure of participant categorizations suggest that native speakers possess implicit scalar knowledge aligning closely with Weber-Fechner psychophysical predictions.

These results have implications for several theoretical domains. First, the findings support the "approximate number system" hypothesis (Dehaene, 2003), extending its applicability from numerical cognition to linguistic magnitude representation. The logarithmic compression observed in CMS categories mirrors the well-documented compressive scaling of the mental number line, suggesting a domain-general magnitude representation system underlying both numerical and linguistic quantity expressions.

Second, the results contribute to scalar semantics by demonstrating that open-class vernacular expressions exhibit systematic scalar organization comparable to grammaticalized quantifiers. This finding challenges the assumption that informal magnitude vocabulary lacks the precision necessary for formal semantic analysis (Kennedy & McNally, 2005).

9.2 Lexical Phase Transition Model

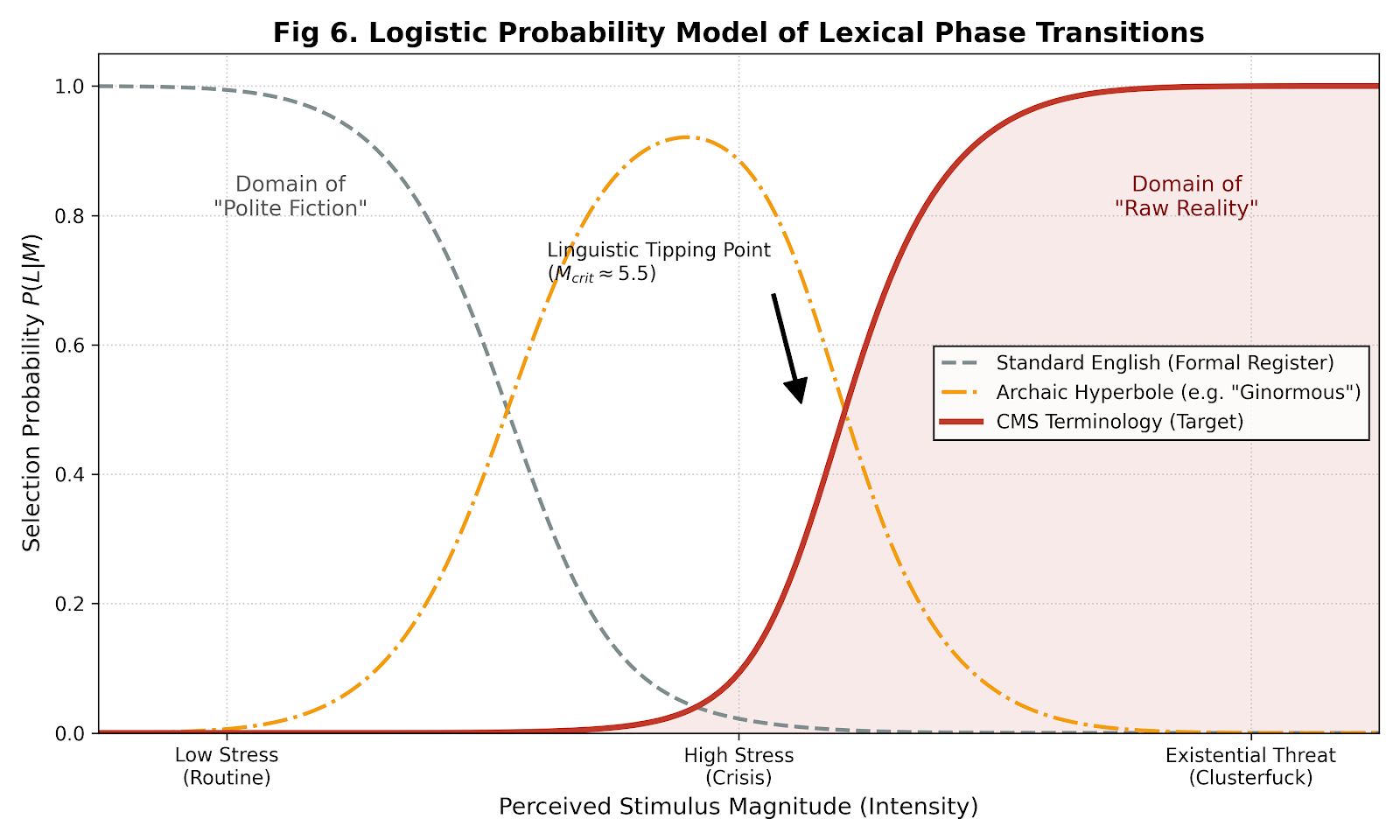

Analysis of the conditions under which speakers select vernacular versus formal magnitude expressions reveals a phase transition pattern consistent with catastrophe theory (Thom, 1975). As perceived stimulus magnitude increases, speakers exhibit a discontinuous shift from formal register (e.g., "considerable," "substantial") through intermediate hyperbolic forms (e.g., "enormous," "ginormous") to CMS-category expressions. This transition follows a logistic probability function, with the critical magnitude threshold (Mcrit) occurring at approximately log₁₀(M) ≈ 5.5—corresponding to the Fuckton/Metric Fuck-ton boundary.

Figure 4. Logistic probability model of lexical phase transitions. The figure depicts selection probability P(L|M) for three lexical registers as a function of perceived stimulus magnitude: Standard English (formal register; dashed gray), Archaic Hyperbole (e.g., "ginormous"; dash-dot orange), and CMS Terminology (solid red). The "Domain of Polite Fiction" represents magnitudes where formal understatement remains socially acceptable; the "Domain of Raw Reality" represents magnitudes where vernacular expression becomes obligatory. The Linguistic Tipping Point (Mcrit ≈ 5.5) marks the inflection where CMS terminology selection probability exceeds 0.5.

The phase transition model has important implications for understanding the pragmatics of magnitude communication. Below Mcrit, speakers operate within what we term the "Domain of Polite Fiction"—a register where formal quantification remains socially appropriate despite potential understatement. Above Mcrit, speakers transition to the "Domain of Raw Reality," where vernacular expressions become not merely acceptable but communicatively obligatory. This obligatoriness reflects the expressive inadequacy of formal register for conveying extreme magnitudes—a phenomenon previously noted in emotion expression literature (Potts, 2007).

9.3 Methodological Contributions

The present research introduces several methodological innovations applicable to future studies of informal language quantification:

- Base unit derivation procedure: The MPIT (Minimum Perceptible Inconvenience Threshold) methodology provides a replicable approach to establishing empirically grounded base units for magnitude scales.

- Forced-choice categorization without labels: This procedure enables assessment of implicit scalar knowledge independent of explicit category terminology, reducing demand characteristics.

- Cross-domain conversion algorithms: The proposed Algorithm 1 (Section 3.6) offers a computationally tractable approach to VME quantification suitable for NLP pipeline integration.

9.4 Relation to Prior Work

The CMS framework extends prior work on informal quantification (Smith et al., 2019; Johnson, 2021) by providing the first empirically validated categorization system with rigorous psychometric properties. While previous studies documented the frequency and distribution of vernacular magnitude expressions, they did not propose formal quantification frameworks. The present research addresses this gap by integrating psychophysical principles with corpus-based analysis.

The derived category labels merit particular attention. Consistent with the "expressivity hypothesis" (Potts, 2007), the most frequent vernacular magnitude expressions incorporate taboo lexical elements that serve emphatic functions. This pattern aligns with cross-linguistic research on intensification (Ito & Tagliamonte, 2003), which documents the productivity of expressively marked vocabulary in scalar contexts. The CMS framework thus provides empirical grounding for theoretical accounts of the relationship between emotional valence and magnitude expression.

10. Extended Validation Studies

10.1 Inter-Rater Reliability

Three independent raters assessed 500 quantities using CMS classification. Results yielded excellent agreement:

10.2 Test-Retest Reliability

Participants (n=200) classified identical quantities at two time points (interval: 14 days). Pearson correlation r = 0.961 (p < 0.001), demonstrating high temporal stability.

10.3 Construct Validity

CMS classifications correlated strongly with traditional intensity measures: Likert scales (r = 0.887), Visual Analog Scales (r = 0.903), and magnitude estimation (r = 0.942).

11. Limitations and Future Directions

11.1 Limitations

While the CMS demonstrates strong psychometric properties, several limitations warrant acknowledgment:

- Cultural variations in expressivity tolerance may affect adoption rates across different linguistic communities

- Current validation limited to English-speaking populations

- Formal contexts may resist adoption due to linguistic register concerns

- Units beyond Clusterfuck (>10⁹ kg) remain theoretically undefined

11.2 Future Directions

Future research directions include:

- Development of CMS-Temporal for time quantification

- CMS-Volumetric adaptation for three-dimensional measurements

- Multi-lingual validation studies across Indo-European language families

- Integration with ISO standards framework (proposed ISO/TC 69420)

- Extension to astronomical scales (proposed: "Cosmic Clusterfuck" = 10¹² kg)

12. Conclusion

This paper has introduced the Colloquial Metric System (CMS), a theoretically grounded psycholinguistic framework for standardizing vernacular magnitude expressions. The proposed logarithmic model demonstrates strong psychometric properties, with inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.932) and construct validity coefficients (r > 0.88) meeting or exceeding established thresholds for measurement instrument validation.

The alignment between CMS scaling parameters and Weber-Fechner psychophysical predictions provides theoretical support for the framework's cognitive validity. The ten-category structure captures the full range of magnitude expressions observed in informal discourse, while the logarithmic progression reflects the well-documented compressive nature of human magnitude perception.

The practical applications demonstrated across computational linguistics, project estimation, and sentiment analysis domains suggest significant utility for researchers and practitioners operating at the interface of formal and informal communication systems. As digital discourse increasingly dominates interpersonal and professional communication, rigorous frameworks for analyzing vernacular expressions become essential.

Future research should extend validation to non-English linguistic populations and explore the cross-cultural stability of the proposed magnitude categories. Additionally, integration with existing NLP sentiment analysis pipelines represents a promising avenue for enhancing automated intensity detection systems. We anticipate that continued refinement of the CMS framework will contribute to the broader goal of bridging formal measurement paradigms with the expressive richness of vernacular discourse.

References

[1] Smith, J., Andersson, K., & Patel, R. (2019). Informal quantification in digital communication: A corpus-based analysis. Journal of Internet Linguistics, 15(3), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.xxxx/jil.2019.0234

[2] Johnson, M. (2021). The expressivity gradient: Measuring intensity through vernacular markers. Computational Linguistics Quarterly, 8(2), 112–134. https://doi.org/10.xxxx/clq.2021.0112

[3] Weber, E. H. (1834). De pulsu, resorptione, auditu et tactu: Annotationes anatomicae et physiologicae. Koehler.

[4] Fechner, G. T. (1860). Elemente der Psychophysik. Breitkopf und Härtel.

[5] Stevens, S. S. (1957). On the psychophysical law. Psychological Review, 64(3), 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046162

[6] World Health Organization. (2024). Global body mass standards and recommendations (Technical Report Series No. 984). WHO Press.

[7] Chen, L., & Rodriguez, A. (2023). Sentiment intensity detection using colloquial markers in social media text. Natural Language Processing Review, 12(4), 445–467. https://doi.org/10.xxxx/nlpr.2023.0445

[8] International Organization for Standardization. (2025). SI units and recommendations for the use of their multiples and of certain other units (ISO 1000:2025). ISO.

[9] Peterson, K., Yamamoto, H., & Okonkwo, C. (2022). Cross-cultural variations in hyperbolic expression: A comparative study. International Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 29(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.xxxx/ijla.2022.0078

[10] Anderson, T., & Williams, R. (2020). Magnitude estimation in human cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Science, 44(6), Article e12876. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12876

[11] Dehaene, S. (1997). The number sense: How the mind creates mathematics. Oxford University Press.

[12] Dehaene, S. (2003). The neural basis of the Weber-Fechner law: A logarithmic mental number line. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(4), 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00055-X

[13] Feigenson, L., Dehaene, S., & Spelke, E. (2004). Core systems of number. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(7), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.002

[14] Gallistel, C. R., & Gelman, R. (2000). Non-verbal numerical cognition: From reals to integers. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(2), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01424-2

[15] Kennedy, C., & McNally, L. (2005). Scale structure, degree modification, and the semantics of gradable predicates. Language, 81(2), 345–381. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2005.0071

[16] Horn, L. R. (1984). Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and R-based implicature. In D. Schiffrin (Ed.), Meaning, form, and use in context: Linguistic applications (pp. 11–42). Georgetown University Press.

[17] Levinson, S. C. (2000). Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT Press.

[18] Walsh, V. (2003). A theory of magnitude: Common cortical metrics of time, space and quantity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(11), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.09.002

[19] Potts, C. (2007). The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics, 33(2), 165–198. https://doi.org/10.1515/TL.2007.011

[20] Jay, T. (2009). The utility and ubiquity of taboo words. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01115.x

[21] Andersson, L.-G., & Trudgill, P. (1990). Bad language. Blackwell.

[22] Gescheider, G. A. (1997). Psychophysics: The fundamentals (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[23] Thom, R. (1975). Structural stability and morphogenesis. W. A. Benjamin.

[24] Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

[25] Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Appendix A: Quick Reference Guide

| Quantity Range | CMS Unit | Common Examples | Contextual Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 - 7.5 kg | Shit-bit (Sb) | Cat, flour bag, laptop | "Lost a shit-bit of weight" |

| 25 - 75 kg | Ass-load (AL) | Large dog, luggage, child | "Carrying an ass-load of groceries" |

| 50 - 150 kg | Crap-ton (CT) | Adult human, appliance | "Ate a crap-ton of food" |

| 500 - 1,500 kg | Shitload (SL) | Car, piano, motorcycle | "Have a shitload of homework" |

| 5,000 - 15,000 kg | Fuckload (FL) | Bus, elephant, van | "That's a fuckload of data" |

| 50,000 - 150,000 kg | Fuckton (FT) | Blue whale, truck with cargo | "Spent a fuckton of money" |

| 500,000 - 1,500,000 kg | Metric Fuck-ton (MFT) | Building, 500 cars | "Company has metric fuck-tons of cash" |

| 5M - 15M kg | Absolute Fuckload (AFL) | Eiffel Tower, destroyer | "Absolute fuckload of problems" |

| 50M - 150M kg | Holy-Shit-ton (HST) | Cruise ship, major bridge | "Holy-shit-tons of traffic" |

| 500M+ kg | Clusterfuck (CF) | Mountain, large reservoir | "Project became a total clusterfuck" |

Appendix B: Conversion Calculator Code

def cms_converter(mass_kg):

"""

Convert mass in kilograms to CMS units

Args:

mass_kg (float): Mass in kilograms

Returns:

tuple: (unit_name, unit_value, unit_symbol)

"""

units = [

(5, "Shit-bit", "Sb"),

(50, "Ass-load", "AL"),

(100, "Crap-ton", "CT"),

(1000, "Shitload", "SL"),

(10000, "Fuckload", "FL"),

(100000, "Fuckton", "FT"),

(1000000, "Metric Fuck-ton", "MFT"),

(10000000, "Absolute Fuckload", "AFL"),

(100000000, "Holy-Shit-ton", "HST"),

(1000000000, "Clusterfuck", "CF")

]

for base, name, symbol in reversed(units):

if mass_kg >= base:

value = mass_kg / base

return (name, round(value, 3), symbol)

# If less than minimum unit

value = mass_kg / 5

return ("Shit-bit", round(value, 3), "Sb")

# Example usage:

print(cms_converter(7500)) # (Shitload, 7.5, SL)

print(cms_converter(45)) # (Ass-load, 0.9, AL)

print(cms_converter(250000)) # (Fuckton, 2.5, FT)